There is a curious thing going on in our backyard.

Well, okay, there are many curious things in that yard, truth be told, but this one came to my attention relatively recently. It didn’t jump out and grab hold of me like some things do—like, say, a Mississippi kite nesting in one of our trees did last year.

This one was quieter and more subtle and only revealed itself when I was attempting to identify an insect in some photographs I had taken.

We have a few wafer ashes (Ptelea trifoliata) in our backyard, ranging from young twiggy things to one that is quite tall and mature.

One of the middling sized ones had many of its smaller branches and twigs covered with white masses that I first mistook for scale insect colonies. Then I noted that wherever the white stuff was, these perky little treehoppers were, too. The hoppers were quickly identified as Two-marked treehoppers (Enchenopa binotata), with their distinctive double-dash marks on their backs and their prominent “horns”, and a little more searching identified the white masses as “egg froth”, which serves to cover up the slits that the hoppers lay eggs in and protect the eggs from predators and the elements.

So far, so good. But at the same time I discovered that my hopper friends were actually considered to be one of a group of species that are differentiated, not by their looks, distance from each other, or even their habits, but rather by the plants they chose to live on once upon a time. It seems that two groups of these insects living side-by-side on trees or shrubs of different species, might also be different species themselves. Enter the so-called Enchenopa binotata “Complex”.

One of the other host species (there can be nine or more, depending on your sources) is the redbud (Cercis canadensis) tree. Well, guess what? One of our smaller wafer ashes is nestled in the loving twigs of a mature redbud tree in our backyard, actually in physical contact with it. The wafer ash had a bunch of treehoppers and egg froth, but I had to search pretty carefully to find any in the redbud. I succeeded finally, but I could count the hoppers on one hand, and they looked lonesome, they did, standing hopeful watch over a couple scanty patches of egg froth.

So, I wondered, how could this strange state of affairs come about? How could several identical-looking populations of an insect in close contact with each other end up on the road to becoming separate species? (In the jargon scientists love soooo much, this is called “sympatric speciation”, I just found out. Now you know, too.)

Well, it seems, once an insect gets used to living and reproducing on a certain species of plant, especially when they lay their eggs in that same plant, things start happening that aren’t so easily undone. Plants don’t always run on the same schedule, for example. Different trees may leaf out at different times in the spring, or their sap might starting running on different timetables and have different types and levels of nutrients. And on and on.

“Life histories of this species vary according to the phenology of their host plants. These treehoppers lay their eggs on its host plant’s branches, as well as spend their juvenile and adult life on one plant. Egg hatching of these treehoppers are tied into the sap flow of their host plants….Species on different host plants have developed allochronic phenologies. This means that species on different host plants have evolved different timing in their life history.”

If hopper eggs on one tree hatch when the sap starts running, then, at any given time, those insects’ life-cycles will be at a different stage than their relatives on a different host that wakes up sooner or later. Then, one tree’s population may start mating before the other tree’s population even gets interested in all that stuff, and, since the females only mate once, the local boys have the advantage. Add in possible nutritional differences and other, maybe unknown, factors affecting life on one plant differently than on the other, and those two hopper populations can start to split apart, even if they can wave hello to each other.

But, hmmmm. Since males can mate many times, what’s to stop those hoppers from hopping on over to a different tree when the females there go courting?

Ah, the power of a love song.

Seems like becoming a new species can be a complicated thing, involving different processes and, of course, enough time to happen. One such process with Two-marked treehoppers seems to be learning new “songs” to serenade each other with—a sort of musical “drift”.

Female and male hoppers call back and forth to each other, using the twigs they are parked on as carriers. Now, we’re not talking transatlantic cables here, but this does seem to work up to a meter or so. As populations separate on different plants, it seems that, just like with people, language starts to change a bit and so do the songs they sing. A male hopper that serenaded his way to success on a redbud tree might strike out totally on a wafer ash, because none of the ashy females are going to fall for such an uncool line. And if they don’t reply, he can’t find them.

Eventually, these and other isolating processes can reduce interbreeding to the point where the genetic make-up of different groups drifts apart enough that mating, even if it happened in the first place, wouldn’t be successful, .

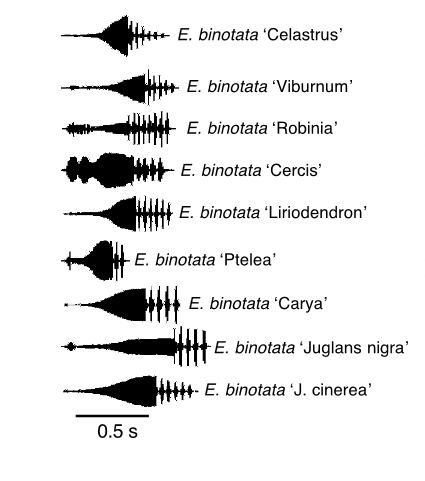

Love calls from hoppers on different hosts have, of course, been recorded, because there is no such thing as privacy, anymore. Below are some graphs of the sounds made by males on different host plants:

And here’s an example of what one sounds like:

Here’s another:

Romantic, hey?

Our E. binotata complex in Eastern North America is estimated to have split off from Enchenopa species in Central America somewhere around 17-18 million years ago in the Miocene age. The known members of the complex seem to have been splitting off from each other from about 0.62 million years back, for the ones choosing walnuts to live on, to as recently as 29,000 years ago for most of the rest. And it still is going on.

Books could be and have been written about this whole complicated process, but, relax, I’m not going to write one here. I just find it fascinating that Nadia and I can step out of our back door into our little backyard and find things going on with a direct line to other continents and unimaginably far-off times, things that shape and are shaped by everything else in the world.

Our humble and messy patch is one tiny place in one tiny slice of time, but it has so much in it, including, in this case, an example of how new species form.

Right in front of our eyes.